En Vogue: What Happened After the R&B Group Lost Its Harmony

The female group of singers hit it big with “My Lovin’ (You’re Never Gonna Get It).” Then, a management dispute erupted, and an arbitrator was tasked with deciding who was gonna get it (the group’s name).

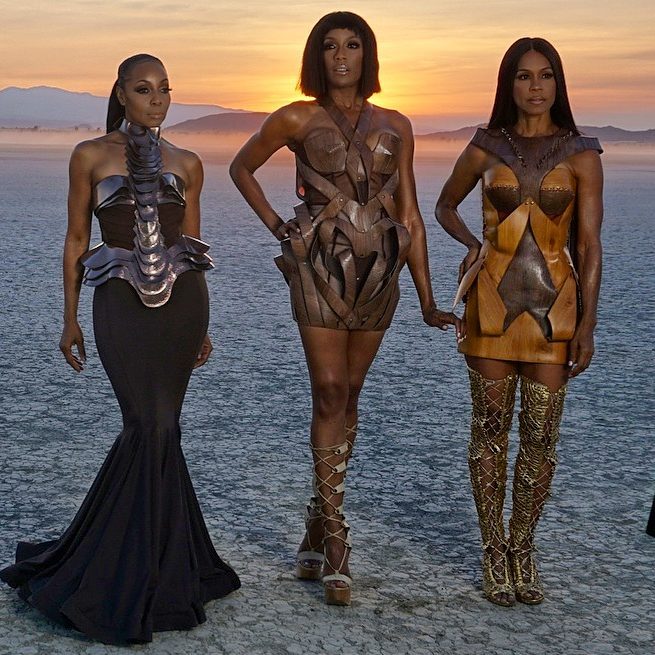

Getty Images

Although most people don’t think of rock bands and R&B groups as corporations, the truth is that many are established by charter and members are equivalent to shareholders. There’s also good reason why it might be best to have an odd number of core members — like 3 or 5 or 7.

In the 1990s, the female R&B group En Vogue burst onto the music scene as a sophisticated reincarnation of the girl groups from a previous doo-wop era. Cindy Herron-Braggs, Maxine Jones, Dawn Robinson and Terry Ellis were the original lineup who produced such hits as “Hold On,” “My Lovin’ (You’re Never Gonna Get It)” and “Free Your Mind.”

By 2012, Robinson had left the group. The three others remained, but were at odds over management. On one side, Braggs and Ellis insisted upon using their man. On the other, Jones wanted her own and refused bookings. So, Braggs and Ellis replaced Jones. And then, Jones re-teamed with Robinson.

Which side would get to use the “En Vogue” name? That was the question that was recently put to an arbitrator. The Hollywood Reporter has obtained a copy of the decision.

To start out, Robert Nau, the arbitrator, didn’t have the easiest of jobs even if his conclusion ended up being pretty simple.

En Vogue became a limited liability company in 2006, and members entered into a written operating agreement. But in 2012, that operating agreement was restated. However, the first page of the operating agreement indicated different parties from the second page, and to make things worse, the agreement referenced the ’06 one, where pages went missing.

In his ruling (read in full here), Nau addresses this before moving to the crux of the dispute.

In 2009, the company hired Joe Mulvihill to be their manager. As such, he was entitled to a 10 percent commission.

That was OK by Braggs and Ellis, but Jones hired her own manager, Julian Jackson, and wanted Mulvihill terminated. The other two wouldn’t comply.

When Mulvihill obtained new bookings for En Vogue, Jones refused to respond. As a result, the group lost bookings, and so Braggs and Ellis replaced Jones with another performer. Then, Jones and Robinson started appearing together.

With two En Vogue groups hitting the circuit, a demand for arbitration was filed last July.

After looking over the situation, Nau determines, “While the Agreement does not expressly state who owns the group name, I find that, by implication and inference, the Company owns all right, title and interest and to the trademark, tradename, service mark and stage name ‘En Vogue.’”

The arbitrator continues, “Claimants [Braggs and Ellis] both approved of the engagement and retention of Mulvihill as the manager of the group. Without the approval of at least one other member of the Company, Respondent [Jones] did not have the right on her own to overrule the decision of the Company to use Mulvihill as the manager of the group.”

Nau rules that Jones breached the agreement by using “En Vogue” but declines to award any damages beyond attorney’s fees and costs.

Essentially, to resolve a fight over lost harmony, the arbitrator has applied the principle of “majority rules.” R&B groups might come and go, but that long-standing legal doctrine will never go out of style.

News

[EMOTIONAL] Snoop Dogg’s Daughter Cori Broadus Makes Fans Cry Recalls Suffering a Stroke in New Special

Snoop Dogg’s Daughter Cori Broadus Details Suffering Stroke While Wedding Planning in New E! Special Snoop Dogg’s daughter Cori Broadus faces a terrifying health scare and major relationship troubles while planning her wedding in first trailer for E!’s Snoop Dogg’s Fatherhood:…

Reba McEntire Fans Call Out Country Star for Perplexing Message

Reba McEntire Fans Call Out Country Star for Perplexing Message on Election Day Many celebrities issued political messages leading up to the 2024 election, but Reba McEntire was not one of them. On Election Day, however, the country star issued a perplexing statement…

[Watch] Reba McEntire Makes A Stuns As She Cozies Up to Boyfriend Rex Linn in Her ‘The Voice’ Chair

Reba McEntire had a special guest on the set of The Voice recently: The first-time coach’s boyfriend and fellow “tot” Rex Linn stopped by. The pair cozied up for a couple of photos in her iconic red chair, and McEntire used the opportunity to solicit votes for…

John Legend Makes A Stun As He Reveals When Blake Shelton Will Return to The Voice

‘The Voice’: John Legend Addresses Whether Blake Shelton Will Ever Return to Show Amy Sussman/Getty Images; Jason Davis/Getty Images) Following Blake Shelton‘s exit from The Voice at the end of Season 23, John Legend is now the longest-tenured coach on the NBC singing competition series. But could…

The $H0CKING Reason Niall Horan Leave ‘The Voice’. Her Is All You Need To Know

Why Did Niall Horan Leave ‘The Voice’ Season 25? Here’s the Real Reason Behind His Exit The former One Direction band member won’t be a judge on the NBC series in 2024. NBC We’ve been independently researching and testing products…

Gwen Stefani Said ‘The Voice’ caused a misunderstanding about she and Blake Shelton relationship

Gwen Stefani Said ‘The Voice’ Edited Footage to Look Like She Was Flirting With Blake Shelton Long Before They Were Together In 2015, both Gwen Stefani and Blake Shelton left their respective marriages. Stefani had wanted to conceal her separation from Gavin Rossdale on…

End of content

No more pages to load